Endometriosis is a painful inflammatory condition where tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus, affecting about 10% of women of reproductive age worldwide. Traditionally, research on endometriosis has focused on hormonal and genetic factors.

However, emerging evidence suggests that life experiences, particularly traumatic events, may also play a significant role in this disease. A large international study published in JAMA Psychiatry in February 2025 has strengthened the link between endometriosis and past physical or sexual trauma, indicating that women with endometriosis are significantly more likely to have experienced such trauma in their lifetime.

Notably, this association appears to be independent of genetic predisposition, suggesting that trauma itself is an environmental risk factor for developing endometriosis. These findings underscore the importance of looking beyond biology alone – considering mental health and trauma history as part of a comprehensive approach to endometriosis care.

Key Findings:

- Higher Trauma Rates in Endometriosis: Women with endometriosis were far more likely to report having experienced traumatic events (especially contact traumas like physical or sexual abuse) compared to women without endometriosis. For example, endometriosis patients had a 16–17% higher chance of having faced sexual assault or witnessed a sudden death, and over a 30% higher chance of a severe life-threatening illness experience, relative to controls.

- Independent of Genetic Risk: The link between trauma and endometriosis remained significant even after accounting for genetic risk factors. In other words, traumatic experiences increased endometriosis risk regardless of whether a woman was genetically predisposed to the disease. No direct gene–trauma interaction was found, implying trauma is a risk factor on its own, not merely a byproduct of genetic susceptibility.

- Shared Genetic Links (Endo–PTSD Connection): Genetic analyses revealed that endometriosis shares genetic correlations with trauma-related conditions, notably post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and aspects of childhood maltreatment. This means some of the same genetic factors may contribute to both endometriosis and the psychological effects of trauma, hinting at overlapping biological pathways.

- Psychological Health and Endometriosis: Women with endometriosis also had higher rates of stress-related or mental health conditions (such as anxiety, depression, PTSD) than those without endometriosis. The new findings build on earlier research that linked endometriosis with conditions like depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. This emphasizes that endometriosis is not just a gynecological issue but can be closely intertwined with mental well-being.

- Implications for Screening and Care: The study’s authors suggest that clinicians should assess trauma history and psychological health in patients with endometriosis. In the future, screening programs for endometriosis might include questions about physical or sexual abuse and other adverse experiences, alongside genetic and physical factors. Recognizing the trauma link could lead to earlier identification of at-risk women and more holistic treatment strategies that address both physical symptoms and emotional health.

Background: Endometriosis and Its Challenges

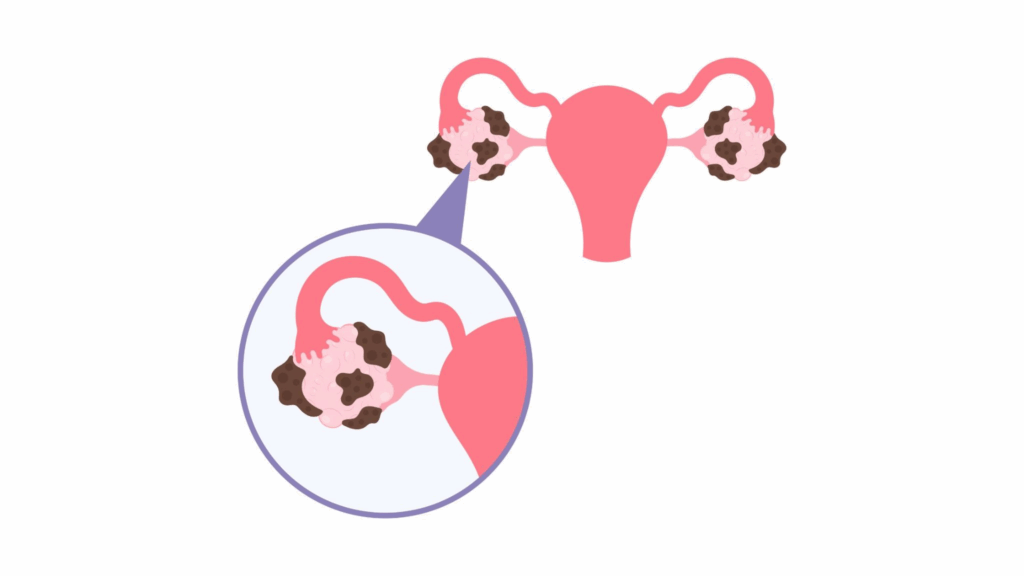

Endometriosis is a chronic condition in which tissue resembling the endometrium (the lining inside the uterus) grows outside the uterus, often on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and other pelvic organs. This misplaced tissue still behaves like uterine lining – thickening, breaking down, and bleeding with each menstrual cycle – but, unlike normal menstrual blood, it has no easy way to exit the body.

The result is inflammation, the formation of scar tissue and adhesions, and intense pelvic pain, especially during periods. Other symptoms include chronic lower abdominal pain, pain during intercourse, and sometimes infertility. Endometriosis affects an estimated 190 million women worldwide, making it a major women’s health issue.

Despite its prevalence, endometriosis can be difficult to diagnose – often taking years for women to receive a definitive diagnosis. Its exact causes remain only partly understood. Genetic factors do play a role; having a family member with endometriosis slightly increases one’s risk. Hormonal factors (like high estrogen levels) and immune system dysfunction have also been implicated in the disease’s development. However, there is growing awareness that endometriosis is a systemic disease with impacts beyond the reproductive tract.

Patients often suffer not just physically, but emotionally as well, due to chronic pain, fertility issues, and the toll of living with a long-term condition. Past research has found that women with endometriosis have higher rates of mental health struggles such as depression and anxiety.

This bidirectional link makes sense: chronic pain and infertility can lead to emotional distress, and conversely, stress and psychological trauma might influence physical processes in the body (for example, through hormonal or immune pathways).

Given this background, scientists have been curious about whether traumatic experiences in a woman’s life could be linked with the development or severity of endometriosis. Traumatic or highly stressful events (such as abuse, violence, or serious loss) are known to affect the body’s stress response systems. Prior studies have shown that severe stress and trauma can lead to long-lasting changes in hormones (like cortisol), immune function, and inflammation – all factors that could potentially influence conditions like endometriosis.

Moreover, as mentioned, women with endometriosis often report higher levels of psychological distress. The question remained: Could trauma actually contribute to the risk of developing endometriosis, and if so, how?

The 2025 International Study

To investigate the trauma–endometriosis connection more rigorously, a team of researchers from the University of Barcelona (along with collaborators in Norway, Sweden, the UK, and the US) carried out a comprehensive study combining observational data and genetic analysis.

The study analyzed data from the UK Biobank, a large biomedical database in the United Kingdom that has detailed health, lifestyle, and genetic information on hundreds of thousands of volunteers. From this resource, the researchers identified 8,276 women with endometriosis and compared them to 240,117 women without endometriosis (controls).

This large sample provided substantial statistical power to detect associations.

Trauma Histories: All participants had answered questionnaires about traumatic and stressful experiences in their lives. The scientists looked at both childhood trauma (such as abuse or neglect when growing up) and adult trauma (such as sexual assault, domestic violence, or other serious adverse events in adulthood).

They categorized trauma into different types, including:

- Contact vs. non-contact trauma: Contact traumas involve direct physical harm or threat (e.g., physical abuse, sexual assault), whereas non-contact traumas might include events like witnessing violence or experiencing a devastating accident without physical harm.

- Interpersonal trauma: events caused by other people (like abuse, assault, or domestic violence) versus non-interpersonal trauma (traumatic events not directly caused by another person’s intentional actions, like natural disasters or serious accidents).

Specific categories such as childhood maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and other stressful life events were also examined.

To uncover patterns in how different traumas co-occur, the researchers used a statistical method called latent class analysis (LCA). LCA groups individuals into hidden subgroups or “classes” based on their trauma exposure profiles. For example, one class might be “mostly no trauma,” another “primarily childhood emotional abuse,” another “multiple severe traumas,” and so on. This helped identify whether women with endometriosis tended to fall into particular trauma-profile groups more than controls did.

Genetic Analyses: Beyond surveys, the study also leveraged genetic data. The researchers performed a genome-wide association study (GWAS) on the endometriosis cases, scanning their DNA for genetic variants associated with having endometriosis.

They also took advantage of results from previous large genetic studies on endometriosis (which included tens of thousands of cases globally) and on trauma-related conditions. In particular, they looked at genetic risk scores for conditions like PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) and childhood maltreatment susceptibility.

By calculating a polygenic risk score (PRS) for each participant (a single summary measure of someone’s genetic likelihood of having a trait, based on many small genetic contributions), they could test whether women genetically prone to trauma-related disorders were also more likely to have endometriosis.

They asked a few key genetic questions:

- Do endometriosis and certain trauma-related conditions share overlapping genetic risk factors? (This was addressed by looking for genetic correlations between endometriosis and, for example, PTSD or depression.)

- Does carrying a genetic predisposition for endometriosis make someone more vulnerable to the effects of trauma, or vice versa? (This was tested by looking for any interaction between the polygenic risk scores for endometriosis and reported trauma exposure – essentially, seeing if the combination of high genetic risk + trauma history led to especially high endometriosis rates beyond the sum of their individual effects.)

By combining phenotypic data (trauma histories, health records) with genomic data, the study aimed to paint a clearer picture of how much trauma matters for endometriosis and through what mechanisms.

Results of The Study

The study’s findings provided compelling evidence that women with endometriosis have endured trauma at higher rates than women who do not have endometriosis. In simple terms, having a history of traumatic stress was associated with greater odds of having endometriosis.

Below, we break down some of the key results:

Overall Trauma Association

Women diagnosed with endometriosis were significantly more likely to report any kind of traumatic experience (in childhood or adulthood) compared to controls. This confirms an association that had been hinted at in smaller studies before: endometriosis and trauma often go hand-in-hand. The new twist is that this study quantifies the link on a very large scale.

Stronger Link with Contact Abuse

When looking at different trauma types, the strongest associations were found with what researchers call “contact” traumas – experiences involving direct physical violation or harm. In particular, physical and sexual abuse stood out. The study noted that endometriosis patients had higher odds of having been victims of sexual assault or physical violence at some point in their lives, relative to women without endometriosis. By contrast, non-contact traumas (like witnessing an accident or disaster) showed a weaker relationship with endometriosis than direct abuse did. This suggests that the type of trauma matters, and those traumas that involve personal violation may have a more profound impact on the body in ways that could contribute to endometriosis.

Examples of Specific Traumas

To put the findings in perspective, here are a few examples reported in the study: women with endometriosis were about 17% more likely to have witnessed a sudden death of someone (a shocking, violent loss), 16% more likely to have experienced sexual assault in adulthood, and 36% more likely to have ever received a life-threatening medical diagnosis (an extremely stressful event), compared to women without endometriosis.

These percentages (which are adjusted for other factors) illustrate the elevated exposure to severe stressors among the endometriosis group. The numbers may seem moderate (e.g. 17% higher risk), but in epidemiological terms these are notable increases given how common endometriosis is – especially when aggregated across many types of trauma.

Trauma Profiles (LCA Findings)

Using the latent class analysis, researchers identified distinct patterns of trauma exposure. They found that women with endometriosis were far less likely to fall into a “no trauma” group compared to the control women.

In fact, healthy controls were more often grouped into a class characterized by having no significant traumatic events in their life (or only very mild stressors), whereas endometriosis patients were disproportionately clustered into classes defined by high trauma exposure. Two classes in particular were enriched among the endometriosis group: one corresponding to emotional and physical abuse history, and another corresponding to sexual trauma history.

For example, one cluster representing people with a background of emotional or physical trauma contained about 8% of the endometriosis patients versus only ~5% of controls – a statistically significant difference. Likewise, a cluster defined by sexual trauma had more endo patients (around 5%) than controls (4%). These percentages may sound small, but remember they refer to fairly severe trauma categories, and even a 1–3% difference, when the groups are this large, is meaningful.

The takeaway is that endometriosis patients were more often found in the “traumatized” subgroups, whereas women without the disease were more often in the “low trauma” subgroup. This lends further support to the idea of a connection between trauma and the development of endometriosis.

Cumulative Trauma Effect

The Research Also Observed a Dose-Response Pattern

Women who had experienced multiple traumatic events (more than one type or repeated traumas) had an even higher likelihood of endometriosis than those with no trauma or a single trauma. In other words, trauma may have a cumulative impact on endometriosis risk.

This suggests that the burden of stress on the body adds up – repeated or diverse traumatic experiences might amplify physiological disruptions (like chronic inflammation or hormonal imbalances) that could contribute to endometriosis triggering or worsening. It also underscores the importance of asking about a range of traumatic experiences, not just one type, when evaluating patients’ histories.

Mental Health Comorbidities

Consistent with prior research, this study confirmed that women with endometriosis are more likely to also report mental health issues such as anxiety and depression-

While the study focused on trauma, this finding serves as a reminder that endometriosis often exists within a context of overall reduced well-being. Chronic pelvic pain can lead to anxiety or depressed mood, and vice versa; thus, many endometriosis patients face a dual challenge of managing both physical symptoms and emotional distress.

This overlap between endometriosis and psychological distress provided a clue for the researchers – if mental health and endo are linked, perhaps severe stress (like trauma) could be a common underlying factor linking the two.

Genetic Insights: PTSD and Childhood Abuse Connections

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study was the genetic analysis, which probed whether the link between trauma and endometriosis could partly be explained by common genetic factors. Indeed, the researchers found evidence that the biology of endometriosis is connected to the biology of trauma-related disorders at the genetic level.

Genetic Correlation with PTSD

The strongest genetic link observed was between endometriosis and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Essentially, women who carried gene variants that predispose them to PTSD were also more likely to have endometriosis. Statistical genetic techniques showed a significant correlation between the genetic risk scores for endometriosis and PTSD. This doesn’t mean one causes the other, but it indicates an overlap – certain genes might influence vulnerability to both conditions.

PTSD is a psychiatric disorder triggered by experiencing or witnessing trauma, characterized by intense fear, flashbacks, and hyper-arousal. The genetic overlap hints that there might be shared biological pathways (perhaps related to how the body handles stress or repairs tissue) that underlie both PTSD and endometriosis.

Genetic Links to Childhood Maltreatment

Similarly, endometriosis showed genetic correlations with childhood maltreatment traits.

This refers to the genetic tendency to have experienced or been affected by abuse or neglect in childhood. It may sound odd to talk about a genetic predisposition to childhood trauma – of course, traumatic events themselves aren’t genetic, but some people may have genetic factors that affect personality, environment selection, or memory, making them more likely to be in situations where trauma occurs or to report it. The study found that the genetic signature of having experienced childhood abuse overlaps with the genetic signature of endometriosis risk.

For instance, one specific finding highlighted by the authors was that women who, as children, felt unloved or hated by a family member or were physically abused by family, had an increased genetic propensity linking to endometriosis. This emphasizes how early-life adversity and the body’s disease processes might be interwoven even at the genetic level.

Other Notable Genetic Associations

Beyond PTSD and child abuse, other trauma-related traits appeared to share genetics with endometriosis as well. The study mentioned correlations with things like the likelihood of having someone to take you to the doctor during childhood.

This particular association is interesting: it suggests that women who lacked caregiver support (perhaps reflecting neglect or poor social support in childhood) might have both higher stress exposure and higher risk of endometriosis, potentially due to reduced medical care or chronic stress effects during formative years. While this specific finding needs more exploration, it points toward the broad idea that social environment in childhood (support vs. neglect) leaves an imprint on long-term health, including gynecological health.

Polygenic Risk Score Findings

The researchers also examined whether a woman’s polygenic risk score for endometriosis (i.e. how genetically predisposed she is to endo) interacted with her trauma history. The results showed that having a high genetic risk for endometriosis did, as expected, increase the odds of actually having endometriosis (validating that the genetic score was meaningful)

However, importantly, there was no evidence that genetic risk and trauma “synergized” or multiplied each other’s effects. In statistical terms, they found no significant interaction between polygenic risk and trauma exposure. What does that mean in plain language? It suggests that trauma raises endometriosis risk across the board, and not only in women who are genetically susceptible.

A woman with low genetic risk but a severe trauma history could still end up with endometriosis, and a woman with high genetic risk who also had trauma would have an additive risk roughly equal to the sum of both factors’ individual risks – not an exponentially higher risk. This reinforces the idea that trauma is an independent environmental factor contributing to endometriosis, rather than just unmasking an underlying genetic tendency.

Gene-Environment Relationship

While no direct gene–environment interaction was found, the researchers discussed an interesting nuance: the concept of gene–environment correlation. This is different from interaction.

Gene–environment correlation means that a person’s genetic makeup might influence the likelihood of experiencing certain environments or events. In this context, it’s possible that women genetically predisposed to endometriosis (or to certain psychological traits) might be more likely to encounter or recall trauma in their lives.

For example, someone with a certain temperament or life circumstances (which can have genetic components) might be at higher risk for abusive relationships or might perceive events as more traumatic – and those same genetics might relate to endometriosis risk. If that’s the case, genetics and trauma can be correlated (occur together) without trauma directly causing endometriosis.

The study’s authors suggest this as a partial explanation: perhaps some genes make individuals both more likely to develop endo and more likely to experience trauma, which could inflate the observed association. However, even with this consideration, the overall evidence pointed to trauma having its own effect on endometriosis development, not wholly explained by genetics.

In short, the mechanisms linking trauma to endometriosis seem to operate on top of genetic predisposition, not simply as a consequence of shared genes.

Why Might Trauma Influence Endometriosis? (Discussion)

These findings challenge us to think about how traumatic stress could biologically contribute to a condition like endometriosis. While the study was not designed to answer mechanistic questions definitively, it opens several plausible pathways and hypotheses:

Chronic Stress and Inflammation

Traumatic experiences, especially in childhood, can lead to a state of chronic stress activation in the body. This is often termed toxic stress when it’s prolonged and unmanaged. Chronic stress can dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis – the body’s central stress response system – leading to altered levels of stress hormones like cortisol. Over time, this dysregulation can influence immune function and inflammation.

Endometriosis is itself characterized by inflammation in the pelvic region. It’s conceivable that trauma-induced immune changes might create an internal environment that makes it easier for endometrial cells to implant outside the uterus or for lesions to grow (for instance, via elevated inflammatory cytokines or reduced immune surveillance against endometrial cells). In other words, trauma could prime the body for inflammation, which in turn facilitates endometriotic growths.

Hormonal Pathways

Stress and trauma also affect hormonal balance. There’s evidence that severe stress can alter levels of sex hormones or how the body responds to them. Endometriosis lesions are estrogen-sensitive (estrogen can fuel their growth).

If trauma affects hormonal regulation, this might indirectly affect the course of endometriosis as well. Additionally, trauma might disturb menstrual cycle regularity or cause gynecological health neglect (someone with trauma might avoid gynecologic exams, etc.), potentially delaying diagnosis or exacerbating disease.

Pain Sensitization

Trauma, especially in early life, can heighten the nervous system’s response to pain – a phenomenon known as central sensitization. Many survivors of abuse or PTSD sufferers have somatic symptoms and heightened pain perception.

If trauma survivors develop endometriosis, they might experience more severe pain, or conversely, women with endometriosis who have trauma might report more pain, reinforcing the association. While this doesn’t explain initial disease development, it does relate to how trauma and endo symptoms could reinforce each other.

Behavioral and Healthcare Factors

Women who have experienced trauma (particularly interpersonal trauma) might have differences in healthcare-seeking behavior. For instance, survivors of abuse might be less trusting of medical professionals or might avoid seeking help for gynecologic symptoms (due to anxiety, PTSD triggers, or socio-economic factors if trauma impacted their life stability).

This could lead to endometriosis going undiagnosed longer, allowing it to progress more severely. The study touched on the importance of caregiver support in childhood – if a girl didn’t have someone to take her to the doctor, her endometriosis (which often begins in adolescence) might have gone untreated for years. By the time it’s detected, the disease might be more advanced. So trauma can indirectly worsen outcomes by creating barriers to care or delays in diagnosis.

Shared Genetic Susceptibilities

As noted, some genetic factors might predispose an individual to both trauma-related conditions and endometriosis. For example, genes affecting how the body manages stress (like those involved in the cortisol pathway, or inflammatory response genes) could, if mutated or regulated a certain way, simultaneously increase vulnerability to PTSD and to endometriosis. If that’s the case, identifying those pathways could be key to understanding the mind-body connection in this disease.

Importantly, the study authors caution that more research is needed to untangle these mechanisms. The current evidence supports a link but doesn’t prove that trauma causes endometriosis. It could be that trauma is one of many factors that tip the scales in a genetically susceptible person, or that trauma exacerbates existing mild disease into a more severe form, etc.

There may also be recall bias – women with chronic illness might be more likely to remember or report past traumas than healthy women (especially if asked in a medical context), which could inflate the association somewhat. The study tried to account for some confounders like socioeconomic status (poverty can increase both trauma risk and health problems) and found the trauma link held strong.

Nevertheless, establishing a clear causal chain will require longitudinal studies (following people over time) and perhaps experimental research in animal models to see if induced stress can trigger endometriosis-like changes. What this study does exceptionally well is illuminate the bigger picture: endometriosis is not solely a hormonal or genetic disease – it may also be a condition influenced by a woman’s life experiences and psychosocial context.

This aligns with a more holistic understanding of health, where traumatic early life events can predispose individuals to a variety of chronic illnesses later on (a concept already well-known in mental health and metabolic diseases, and now extending into gynecological disease).

Implications for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Patient Support

The discovery of a strong trauma linkage has practical implications for how we approach endometriosis on multiple fronts:

1. Screening and Early Detection: Clinicians and public health experts could consider integrating trauma history questions into screening tools for endometriosis. If a patient (or even an at-risk adolescent) reports a history of physical or sexual abuse, it might raise a flag to be vigilant for endometriosis symptoms like pelvic pain or menstrual irregularities.

As one researcher suggested, it may be possible to design early endometriosis screening programs that look not only at genetic markers or clinical signs, but also at personal history of trauma as a risk indicator, thereby identifying and treating the disease more proactively.

Early detection is crucial in endometriosis because delayed diagnosis (currently the norm) often means years of unmanaged pain and disease progression. By recognizing trauma survivors as a potentially higher-risk group, healthcare providers might achieve earlier diagnoses for them.

2. Holistic Patient Assessment: For patients already diagnosed with endometriosis, these findings highlight the importance of assessing their mental health and trauma history as a standard part of care. Rather than treating endometriosis narrowly as a reproductive system disorder, doctors and specialists (like gynecologists) should be aware of the psychological dimension. Routine screening for depression, anxiety, or PTSD symptoms in endometriosis patients could be beneficial.

Patients might under-report trauma unless asked directly, so creating a safe space for that discussion is key. Knowing a patient’s trauma history can also inform more sensitive, trauma-informed care – for example, understanding that a pelvic exam might be particularly distressing for a sexual assault survivor with endometriosis, and taking steps to make the process more comfortable.

3. Integrated Treatment Approaches: If trauma contributes to endometriosis risk and potentially its severity, then addressing the psychological aspects could become a part of endometriosis management. This might include offering mental health support, such as counseling or therapy (for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy or trauma-focused therapies), as a complement to medical treatments like hormone therapy or surgery for endo.

Stress-reduction interventions – like mindfulness, stress management techniques, or even medications to address PTSD symptoms – could conceivably improve not only mental well-being but possibly endometriosis outcomes too (for instance, some studies suggest stress reduction can alleviate pain perception and inflammation). In the future, we might see more multidisciplinary care for endometriosis patients: teams that include gynecologists, pain specialists, and psychologists or psychiatrists working together.

4. Patient Education and Empowerment: Awareness of the trauma link can be validating for patients. Many women with endometriosis have faced skepticism about their pain or had their symptoms minimized (“it’s just in your head” or “stress is causing it”). The new research sends a nuanced message: psychological trauma is not causing women to “imagine” their pain – rather, trauma is linked to very real, organic changes in the body.

This can help reduce stigma. It tells patients that if they have a history of trauma, it’s nothing to be ashamed of and it’s relevant to mention it to their doctor because it could be part of the puzzle of their illness. It also underscores to society that diseases like endometriosis have psychosocial components, and supporting women’s safety and mental health is part of preventing physical disease in the long run.

5. Policy and Advocacy: On a broader level, these findings might encourage policymakers and healthcare systems to invest more in women’s mental health as part of reproductive health. For instance, programs that screen for domestic violence or childhood abuse in healthcare settings could be linked with follow-up for potential chronic health issues, including endometriosis. It further justifies a push for trauma-informed care in all medical fields.

Additionally, advocacy groups for endometriosis may use this evidence to argue for more comprehensive care models and research funding that examines environmental factors in endo, not just looking for a drug cure.

Conclusion

The 2025 study published in JAMA Psychiatry provides robust evidence that traumatic experiences are associated with a higher risk of endometriosis, independent of genetic predisposition.

It bridges the gap between mental health and gynecological health, affirming that a woman’s life history – her hardships and stressors – can leave an imprint on her physical well-being. Endometriosis, long understood primarily as a hormonal and immunological disorder, must also be seen through a psychosocial lens. Childhood abuse, sexual violence, and other serious stressors are not just psychological footnotes; they are integral factors that may shape the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

From a scientific perspective, this research opens up new avenues to explore how stress and the immune-endocrine system interact in the development of disease. From a clinical perspective, it urges healthcare providers to treat patients with endometriosis in a more comprehensive manner – addressing not only their pelvic pain and infertility, but also asking about and tending to their emotional pain.

As Dora Koller, the study’s lead author, noted, these results “challenge established paradigms” by uncovering links between endometriosis and trauma-related conditions like PTSD. And as co-author Marina Mitjans emphasized, they highlight how childhood and adult trauma may contribute to endometriosis through mechanisms seemingly independent of genetic risk. For women suffering from endometriosis, the hope is that this knowledge will translate into earlier detection and more effective, empathetic care.

If you have endometriosis and a history of trauma, know that the two might be connected – and it’s important to share that history with your healthcare team. If you have a history of trauma and are experiencing pelvic pain or gynecologic symptoms, it may be worth discussing endometriosis with your doctor.

Ultimately, this research reinforces a holistic truth: the mind and body are deeply interconnected. Healing one often requires caring for the other. By acknowledging the scars that cannot be seen, we may better treat the pain that can.

References

- Koller, D., Løkhammer, S., Goroshchuk, O., et al. (2025). Observational and genetic analyses of traumatic experiences and endometriosis. JAMA Psychiatry, 82(4), 386–394. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4694. (Original research article reporting the study’s findings.)

- University of Barcelona. (2025, February 5). New evidence strengthens the link between endometriosis and traumatic experiences. Medical Xpress. Retrieved from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-02-evidence-link-endometriosis-traumatic.html

- Sidharthan, C. (2025, February 10). Study reveals link between traumatic experiences and endometriosis risk. News-Medical. Retrieved from https://www.news-medical.net/news/20250210/Study-reveals-link-between-traumatic-experiences-and-endometriosis-risk.aspx

- McGovern, G. (2025, May 9). Study finds endometriosis may be linked to traumatic experiences. Pharmacy Times. Retrieved from https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/study-finds-endometriosis-may-be-linked-to-traumatic-experiences